- Reviews

- Power List 2024

- Cannes 2024

- In-Depth Stories

- Web Stories

- News

- FC Lists

- Interviews

- Features

- FC SpecialsFC Specials

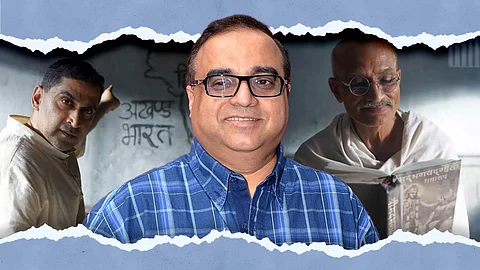

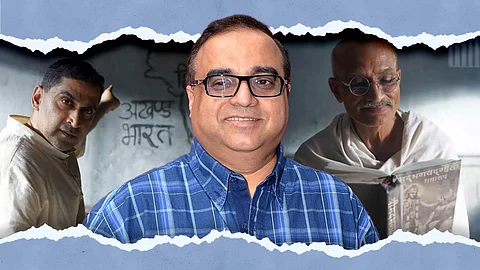

Director Rajkumar Santoshi’s new film was still weeks from release when we spoke, but he was already thinking of his next project. He rarely looks back at it or rewatches any of his films again, he told me and spoke about his next project, which is tentatively titled “Lahore 1947”, stars Sunny Deol and is based on the play “Jis Lahore nahi Vekhya” written by his current collaborator Asgar Wajahat. He also intends to make a mythological in the near future. “While others are busy creating universes, I just want to make good films,” he said.

If Santoshi’s name reminds you immediately of Andaz Apna Apna (1994), then the fact that his new film is Gandhi Godse: Ek Yudh will feel like a stark change of pace. However, if you look back at his filmography, then it’s clear that this is not a director you can pigeonhole. Santoshi is an anti-auteur — no two films of his share a similar aesthetic sense. He’s made films as diverse as Damini (1993) and Andaz Apna Apna in the Nineties. Then, he didn’t make another comedy until the Ranbir Kapoor-Katrina Kaif starrer Ajab Prem ki Gazab Kahani (2009). Following the failure of Phata Poster Nikla Hero (2013), Santoshi seemed to have disappeared and now he’s back, with a story that speculates about the past.

“Gandhi Godse: Ek Yudh adds a new chapter to the history, reimagining the times if the two men were alive and met again for a conversation. We have given them both a platform to express themselves and give clarification on many subjects their followers remain divided about,” said Santoshi. When asked about his absence in the past few years, he said he’d spent his time writing and developing concepts. He also rued how corporatisation is changing film production. “There are more proposal makers these days than filmmakers,” said Santoshi. “There is little attempt to stay original in our stories. It’s upsetting how casually some makers choose to copy their entire scripts off some Korean or Western film or remake hit films from South.” Santoshi will have you know none of his 14 films are remakes or plagiarised. The closest he came to a rehash was with China Gate (1998), a film about the redemption of a few old Army men who were dishonourably discharged after a failed mission, which was very loosely inspired from The Magnificent Seven (1960).

Santoshi sounded equally exasperated by the way current filmmakers depict violence in their films. “Besides the action sequences being mindless in their treatment, it’s the way the heroes seem to enjoy and relish the idea of killing that bothers me. Violence cannot ever be glorified in any capacity.” In Santoshi’s debut film Ghayal (1990), the protagonist Ajay (Sunny Deol) is driven towards violent retribution only after being stomped over by a system that has no empathy for a common man. A few years later, Santoshi made Ghatak (1996), which had a similar theme. “When my characters resorted to violence, there was always a strong justification for it. It came from a place of anger. They were never smiling while they killed the bad guys,” he said.

The moral centre visible in many of Santoshi’s films may have its foundation in the director’s early days in the film industry. Santoshi had begun his career assisting filmmaker Govind Nihlani on films like Aakrosh (1980), Ardh Satya (1983) and Party (1984). Talking about his days of struggle in the late Eighties, Santoshi credited Nihlani for providing him a safety net while he pitched his concepts, hoping for a break. “I would tell him to always keep a place open for me if things don’t work out and he would sweetly oblige. Whatever I know of film-making and it’s discipline, it's because of Govind Ji,” he said.

Many of Santoshi’s films show an interest in socio-political themes. Lajja (2001) is a tapestry of four stories, albeit a bit heavy-handed, that underlines the oppression faced by women in a seemingly modern society. One of the stories features Janki (Madhuri Dixit), a spunky theatre performer, who decides to question the moral choices of Lord Ram while enacting Ramayana on stage. The audience erupts into fury, now baying for Janki’s blood, and the narrative concludes with Janki being sent to a mental hospital because she’s considered mentally ill. It feels almost unthinkable to present a story like that today. (Santoshi said he’d faced resistance at the time of film’s release as well, with his effigy being burnt by many people, but the Central Board of Film Certification had not posed any obstacles.)

Khakee (2004) too captures the angst of Anand Srivastava (Amitabh Bachchan), a senior underdog cop who learns the man he is escorting to Mumbai, is not the terrorist that he’s been framed to be by the political-police nexus that is exploiting this man’s Muslim identity. “That still happens, and it’s very saddening,” said Santoshi. “We should never be divided on the basis of caste or religion. One shouldn’t be punished for the religion they are born into.”

Gandhi Godse: Ek Yudh is not the first time Santoshi is telling a story with Gandhi as an integral part of the plot. His The Legend of Bhagat Singh (2002), which remains one of the more memorable portrayals of Bhagat Singh and the other unsung heroes of India’s freedom struggle, offered a critical look at Gandhi. In contrast, his sophomore film Damini begins with a Mahatma Gandhi quote, about one’s conscience being the biggest court of justice, and Santoshi crafts his entire narrative and the protagonist’s journey around the same principle. Ghatak too makes use of Gandhian values as the moral foundation for the protagonist Kashinath (Sunny Deol) and his eventual disillusionment with the system.

Keeping this in mind, Gandhi Godse: Ek Yudh feels like a sharp shift in Santoshi’s filmmaking. When asked about this, Santoshi said he remains a supporter of Gandhi’s stand on non-violence, but that he also prides himself on being “a History student, first of all.” “Both Gandhi and Godse are figures who have been extremely misunderstood and misquoted for decades, and had no way to explain themselves on many issues. It is the right of the audience to know the objective truth, and this film is an honest attempt to capture their true personalities, and to help the audience understand them better,” he said.

Santoshi acknowledged that Nathuram Godse has seen an upswing in his popularity in recent times, but he pointed out that most of Godse’s contemporary supporters don’t know the entire truth about him either. “One is free to support Godse, but only after knowing the complete picture — not just because he killed a political leader you did not admire,” he said. As far as a potential backlash to Gandhi Godse: Ek Yudh is concerned, Santoshi said he was not afraid. “This is a democratic country, and everyone is entitled to have any opinion or bash a film. But I request that they watch it first,” he said.