- Reviews

- Power List 2024

- Cannes 2024

- In-Depth Stories

- Web Stories

- News

- FC Lists

- Interviews

- Features

- FC SpecialsFC Specials

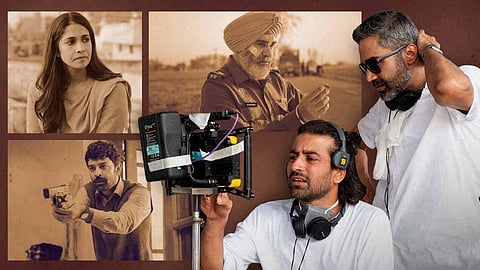

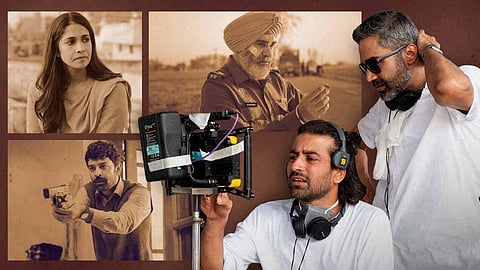

Considering the tremendous critical acclaim he received for Paatal Lok, it would seem natural for writer (and now producer) Sudip Sharma to return to the world of crime and disgruntled police officers for his next project. Except Sharma is among those who have had enough of crime. “I’ll be honest: Most of the time, it turns me off now,” he said during a conversation with Film Companion. In fact, when he finished Paatal Lok, Sharma was quite sure he didn’t want to work on another investigative drama. The same is true of Gunjit Chopra, who was part of Paatal Lok’s writing team. By the time the show was done, Chopra said he “didn’t want to see” crime. Yet the story that Chopra came up with in collaboration with writer Diggi Sisodia, has a dead body with a bludgeoned head in its opening scene. “It just came out this way,” Chopra said wryly of Kohrra. “I had a lot of Punjab in me and I had to put it out. It’s just that it came out in a way that it’s a police procedural.”

For all the villainy and cruelty that crime fiction may contain, the genre is actually rooted in optimism. The investigation of a crime is effectively a process of restoration. If the criminal act creates a disruption, order is restored through the guilty being exposed and brought to justice. Especially when the detective is a police officer or collaborates with the police, the message conveyed by the story is that the institutions are effective and the social contract remains in place. Kohrra offers few such assurances. Instead, it’s a close look at a world riddled with violence, where the lines between good and bad are terribly blurred, and where the authority of institutions is threatened by widening fault lines. With multiple dead bodies and many troubled people who are chafing against the restraints that hold them back, Kohrra is more of a portrait of Punjab than it is a police procedural. “The crime story is the peg on which you hang this to get it made,” said Sisodia. “For us, it was always a human drama.”

Kohrra follows Balbir Singh, a sub-inspector with Punjab Police, who is tasked with solving the murder of a man who turns out to be a British citizen of Indian descent. The dead man had come with his parents and best friend to the small town of Jagrana, to get married. The investigation is slow and it becomes a lens through which to see a society: Its dominant but hapless men, the shadows cast by the past, helpless mothers, the desperate sadness of the younger generation, and the lies that hold this world together. The brilliance of Kohrra is in the worldbuilding and the way details convey a wealth of information without being obvious. For example, the police meet the dead man’s fiancée at a place called Amreeka Return Café, a dig at the young woman who is determined to marry a non-resident Indian. At the café, the younger constable orders a hazelnut frappé, whose exotic otherness makes it seem aspirational. Its allure is in its cosmopolitan foreignness and just the placing of this order hints at the constable’s ambition, especially since accompanying her is Balbir who orders nothing. Kohrra never loses sight of the crimes that need solving — along with the murder, the police have to find the best friend, who is missing — but the whodunit is less compelling than the other stories and secrets that surface in the course of the investigation. Kohrra’s persons of interest are Balbir, his partner Garundi, their families as well as the people connected to the victim.

Playing Balbir is Suvinder Vicky, whose previous credits include Meel Patthar (2020), Udta Punjab (2016), the series CAT and a blink-and-miss-it scene in Paatal Lok. As the grizzled and seemingly unflappable policeman who ties his turban with neat precision and whose personal life is unravelling, Vicky is a revelation. Towards the end of Kohrra, there’s a party scene. An electronic beat drops, a song unfurls and Balbir joins a group of dancing men. It’s a moment that begins on a joyous note, with Vicky looking happy and relaxed. Within seconds, he’s gazing blankly while his body moves with loose disconnect. From his glazed expression, it’s clear Balbir is lost to the present. It’s one of the many scenes in which Vicky brings together disparate aspects of Punjab into the body of his performance (quite literally in this case), creating a masterful portrait of a broken patriarch.

“I knew that there is something very very deep in that actor and I wanted to tap into that,” said Sharma, who is credited as co-creator and executive producer of Kohrra. “Right around the time that we finished writing, in my head it was, ‘OK Suvinder Vicky is playing Balbir Singh’,” said Sharma. “Then it was just about convincing the studios that he can work for it.” The other two people that Sharma knew he wanted for Kohrra were Barun Sobti, who plays Balbir’s macho sidekick Garundi, and director Randeep Jha. “Barun actually came because I’d seen Randeep’s film, Halahal (2020),” said Sharma. “In fact when I saw Halahal, I thought ‘OK I need to work with Barun Sobti and I need to work with Randeep Jha.’ It kind of just followed from there.”

Jha, whose last project was the extraordinary Trial by Fire, knew he wanted to work with Sharma once he’d read Kohrra’s script. The world in which Kohrra is set felt refreshingly unfamiliar to him, despite north India’s badlands having become a stomping ground for a number of recent shows and films. “I hadn’t seen these characters. For me, they were new. I’m not that familiar with Punjab so this was all very new to me. It surprised me,” Jha said.

Remembering the first time he read the script Sharma had sent him, Jha kept using the word “kamal”, which translates to “miracle”. “I had to read it twice,” he said. “There was so much subtlety in it. It was written in a way that made me think, ‘There are so many layers to this’.” As a director, he was immediately drawn to the way the story sought to immerse the audience in Jagrana and the lives of the characters. “It took you into the heart of those relationships. It went into the human aspect — the hypocrisy, complexities; it explored all this so beautifully, so gradually, that you didn’t even realise what it was doing,” said Jha. “After a point, you practically forget that these are (fictional) characters with whom you’re travelling.”

Jha tried to hold on to that feeling of realism and novelty when filming the show. “I was always conscious that I need to try and find different aspects to explore visually,” Jha said, while talking about his response as a director to the glut of crime fiction on streaming platforms. “You can do a scene in a thousand different ways, but the problem is that those thousand different ways have already been done. So then you have to search for something that is intrinsic to you in the way you’re shooting the story.” Instead of imposing stylistic flourishes to the show’s visuals, Jha decided “jaisa hai waise hi shoot kar lete hain (let’s shoot scenes as they are)”. The result is a show in which Jha utilises all the moving parts to great effect and highlights how well-observed the writing is. The elegance of cinematographer Saurabh Monga’s visuals doesn’t feel intrusive. Every location feels lived-in and reflects something of the people inhabiting it. A haunting background score by Benedict Taylor and Naren Chandravarkar makes brilliant use of harsh, discordant melodies. The tension builds at a slow, steady and stifling pace as it pulls the audience deep into the troubled heart of the story and its characters.

There’s an authenticity to Kohrra that makes it difficult to imagine this story unfolding as it does anywhere other than Punjab. “It’s just got an identity of its own like no other state in India. There’s just something very interesting and attractive about that as a storyteller,” said Sharma. For Chopra and Sisodia, the show allowed them to paint a portrait of contemporary Punjab, showing both its grace and its cruelty. “I’m a lover of that state,” said Chopra, sounding almost bashful. “I find it very interesting where Punjab is now, where they’ve reached with the Green Revolution, with the Khalistan movement and all that,” he said, adding that a lot of research has gone into the writing of Kohrra. Bringing the writers’ intentions to life is some inspired casting that doesn’t care for the gloss of celebrity. The closest Kohrra comes to a recognisable face is with Sobti and British actor Rachel Shelley who played the role of Aamir Khan’s almost-love interest in Lagaan (2001). The cast of unknowns serves Kohrra well and most minor characters don’t betray any artifice. Instead they seem to belong in Jagrana, which goes a long way in making the viewer feel forgiving towards the show in the few moments when it stretches credibility or leans into clichés.

For Sharma, it was crucial that the realism of Kohrra acknowledge the multiplicity of Punjabi society. “As much as I love some of these indie films that have come out of Punjab, I’m not sure if that’s also a true representation. Similarly, that balle-balle-shaava-shaava representation is also not a true representation,” said Sharma, adding that the real Punjab is somewhere in between. The investigation allows Balbir and Garundi to take the viewer inside mansions as well as hovels, while paying attention to those who live on the margins as well as those who occupy positions of power.

Violence is a thread that runs through Kohrra, connecting what seems otherwise disconnected. Brutality is accepted as normal and unremarkable. Screams of people being tortured during interrogations become background noise. Pain and trauma are passed down generations. The dead haunt the living. Yet the darkness never overwhelms Kohrra, which is frequently hilarious. The tone shifts with dazzling smoothness, flitting from grim to funny to ominous without ever feeling jarring. “A lot of it is Punjab,” said Sharma. “There is an inherent sense of humour in the land and in the people.” Even while adding levity to a moment, the humour in Kohrra serve to highlight contrasts and add to characterisation. For instance, early on in the show, Garundi asks the dead man’s fiancée if she knows the code to unlock his phone. His face is too mangled for the phone to recognise it, he tells her matter-of-factly. It’s a hilarious moment that also shows how insensitive and carelessly cruel Garundi can be. He’s the good cop who behaves like a bad cop, but is at his core a good guy (give or take some custodial violence and adultery).

By the end of the show, when Kohrra lets the audience in on what happened, there’s little sense of the relief or vindication that conventional crime fiction offers. Instead, a blanket of despair and sadness settles over everything. The sun is shining and the fog has lifted, but the clarity it brings isn’t comforting or hopeful. In its final moments, Kohrra brings together past and present, forging an emotional connection between two characters who seem like polar opposites. Unlike most Indian crime shows, there is no cliffhanger or promise of a second season though Sharma hinted at the possibility of a continuation. “We’re all up for it if called upon to perform the duty once again,” Sharma said with a grin. For him, Jha, Chopra and Sisodia, streaming has become the more comfortable and exciting space to work in, and mainstream films pale in comparison. “You just feel at the end of it (a show), I did something that fully engaged me for these two or three years. I used all the powers and talent that I have to make something,” said Sharma. “There’s something just very satisfying as a writer-creator about that. Apart from the whole practical aspects of it — they will let you make shows with Suvinder Vicky; they’ll not let you make films with him. I would rather work with these actors that I really want to work with rather than chase stars who refuse to answer my calls.”