- Reviews

- Power List 2024

- Cannes 2024

- In-Depth Stories

- Web Stories

- News

- FC Lists

- Interviews

- Features

- FC SpecialsFC Specials

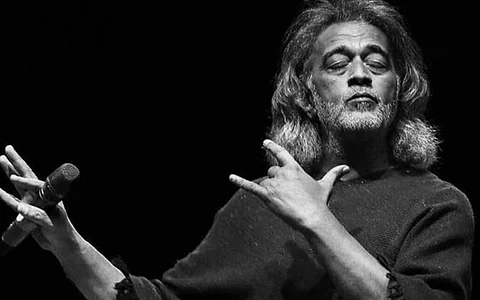

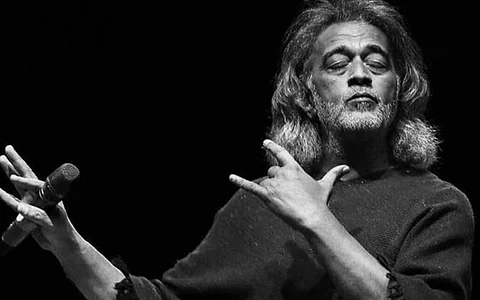

In the throes of the COVID-19 pandemic, suddenly came the nostalgic reprieve of Lucky Ali's sufi-sandpaper voice. A video of him serenading unmasked tourists on a Goa beach with 'O Sanam', the smash hit song from his debut album Sunoh (1996) went viral. It begins with him strumming the guitar, messing up, owning up, and getting back to it again.

He lets his cloistered, mostly seated, mostly young audience complete the lyrics of the song. A girl in the background swiped tears from her eyes, as others, recording him on their phone didn't know whether to look at him on their phone-screen or to look at him as he was, in front of them, eyes darting restlessly between the two.

His seventh and last studio album was Rasta Man in 2011. In between there was a Malayalam song, a Kannada song, and then a retreating from the radar, pushing up briefly for air with AR Rahman's sunny, longing 'Safarnama' in Tamasha (2015), and then again, radio silence. In 2019 he released a song with Israeli musician Eliezer Cohen Botzer, and followed up with another Botzer collaboration last month. He turned 62 last year, and is armed with that sincerity that can only manifest as indifference to commercial imperatives of consistent output; Ali is toeing a different line.

It has been 25 years since Sunoh released on May 6th, 1996. 'O Sanam', the song on which the popular music video set in Egypt was filmed, was the first of 10 songs on the album. Seismic shifts in trends, taste, and talent have taken place since. Ideas of stardom, artistry, and rhythm have taken a hair-pin bend. In this cultural swerve, to love 'O Sanam' is to love the song as one loved it back then, tinted with nostalgia and memory. To listen to it today is thus not just about responding to its melody, and its lyrics, but to the experiences embedded within it—a simple, consummate kind of yearning.

When Sunoh came out, in 1996, the music industry was in thick ferment. At a time when Hindi movie music accounted for more than 80 percent of music sales, there was a sudden burst of energy. Just two years ago, in 1994, in a frenzied hullabaloo of 20 days, Channel V was launched by Star TV network. The idea was to have a channel that was local in content, but international in aesthetic. The Hinglish universe of Quick Gun Murugun, and Jaaved Jaaferi's Hip Hop Hingorani and Vengeance Veerappan was lapped up. It was getting about 37 million viewers every month.

Then a year later in 1995 Alisha Chinai's album Made In India became the first non-film album to break unit sales records in India, selling more than 5 million copies. Then, MTV, which was launched in India in 1991 but failed to capture the Indian imagination by playing Nirvana and classic 80s music, was re-launched in 1996 with a new formula of "East-West masala". It worked.

The music scene was evolving beyond Hindi films. Any music that was popular outside of the purview of films became "Indi-pop" (Indian-pop), a genre unto itself. Even Asha Bhosle, the toast of film music, decided to release a pop album.

A lot of sequencing and remix was on the rise. Ankur Tewari, the musician, then a college student in Bhopal, noted the sudden surge of 'Jhankar Beats', which were drum beats played on octapads artificially inserted into film music. T-Series was at the forefront of this. Tewari noted, "It had a strong treble value. I remember I asked someone about it and they said it cuts through the noise, so the truck driver can listen to these songs. Everyone was listening to music through cassettes, a lot of which was traveling via highways through truck drivers and bus drivers taking it from one place to the other."

In the midst of this came Lucky Ali, just a guy with a guitar and some tunes, and that voice which was unworried, untrained, and yet bristled the insides of the listener. "His voice texture is quite unique—it somehow cuts through everything and gets to you. Exactly what was happening with the remix beats, but here you didn't need the beats because his voice was doing it," Tewari, who has over the years become close with Ali, exchanging recordings of music for feedback, noted.

BMG Crescendo, the label introducing him, were pitching him as a "singer-songwriter". The music critic Narendra Kusnur noted that this wasn't common in those early days of Indi-pop. "Singers usually had someone else doing the music. Alisha Chinai had Biddu doing the music, Daler Mehndi had Jawahar Wattal." This was the added allure of Ali — that the melody came from a place of deep feeling, and not performed fiction. The lyrics for his songs, simple yet profound, curling almost within the boundary of the tune, were written by Syed Aslam Noor.

Ali's soundscape was also striking for its time— it was more spare, with little instrumentation. It set the template that would be followed by Silk Route and later KK's Pal (1999). When Tewari would come to Mumbai two years later to pitch his demos, he didn't have to convince music producers about the nature of his songs that weren't sequenced, programmed, or remixed. Ali, who had the first-mover advantage, so to speak, had convinced music producers of the success of spare music in India. Even Ali noted the importance of releasing Sunoh in 1996 — that it "happened at the right time."

Around 1995, Mikey McCleary, the producer of Sunoh, was working in a studio in Soho, London. Originally called the Trident Studio it was famous for recording songs of The Beatles, David Bowie, and Queen, "I had found a job there when Lucky just knocked on the door and said, 'Hey, I am your new brother-in-law'."

McCleary's sister had just gotten married to Ali, but he didn't know much about the details, since she only informed everyone after the marriage took place. They chatted for a bit when Ali told him that he had come to London to record a few songs, but the studio of the people he was working with burned down and he hadn't much going on. McCleary told him to come back over the weekend so they could "play around with the songs, experiment with it."

"At that time, it was about doing something to show my parents that I was not bekaar. That I have thoughts. I have goals. Maybe I am not able to express it except through music." — Lucky Ali

Ali played his rough cut of 'O Sanam' and 'Sunoh', the first two songs on the album, on the guitar. McCleary recorded his voice, replayed the guitar parts, and reworked the chords. He then used samples of other instruments — where you reuse portions of a sound recording from another recording. Many of the samples were played by McCleary himself from the keyboard, "I was just guessing at that time with sounds I thought sound good." There were no live instruments used for this album other than the guitar, and the keyboard. McCleary experimented with reverb and echo like the opening of 'Sunoh', and did not use the conventional tuning of the guitar, producing a more "world-music" feel. Samples of Udo pots, African drums like the Maktab, were used in 'O Sanam', along with log drums and Djembe. Some flute lines were added, "I was going with whatever instincts I had for what sound I wanted to create."

Ali went back to India to show the recordings to studios. He returned to London a few months later to record the remaining album. McCleary was given full control over the musical arrangement. "Ali would just be there, really. The creation of the arrangement was in my hand; he would react to things and that would help. He was very open, he didn't have any specific kind of concept in mind. He was excited, I think, that his music was being re-interpreted in ways he wouldn't have imagined." For example, McCleary used whale sound samples to bookend 'Tum Hi Se'.

"That was that. He went back to India and 6 months later after it was released I heard from various people in India that the album is becoming quite popular," says McCleary.

The minimal arrangement, by Indi-pop standards, was a direct descendant of McCleary's influences, like Bob Dylan. He didn't think what they were producing at that time was radical. It was only when he came back to India that he could see how different their sound was, "certainly different from film music which at that time."

The strength of the simplicity came from both the spare production, and Lucky's unique vocals, "To this day when you hear Lucky's voice you can distinguish it quite clearly. It's two things, really — there's a comfortingness and sincerity to his voice, and second, there is a distinct sound, a distinct grain to his voice. I have never heard anyone who could impersonate his voice," he adds.

It was this style that calcified inseparably with his voice, creating the mythic, iconic artistic figure we often think of when we think of Lucky Ali. Part of the visual language of this style came from the music video of 'O Sanam', directed by Mahesh Mathai, which gave expression to Ali's nomadic nature.

In 1995, it had been more than ten years since the ad-filmmaker Mahesh Mathai had last spoken to Lucky Ali. They had studied together for a year in high school. Ali was a famous boy because his father was comedy legend Mehmood and his aunt was Meena Kumari. But Ali had moved around schools before and since, and so they lost touch, till they met again after they finished school. "We had a few months of holidays when we met again. He had grown long hair, and learnt to play the guitar — he was the cool one among us. He would sing, not compositions but covers. Thereafter I lost touch with him completely."

And then, in 1995 Mathai got a call from him out of the blue. Ali had recorded an album and wanted him to hear it. At 4D Studios in Century Bhavan, Worli, Ali who had all the songs recorded on a CD, rare in those days, played the entire album. He had been talking to different record labels without much success. Amitabh Bachchan Corporation Limited (ABCL) held onto his album without releasing it for 6 months and Ali asked for the album back.

Mathai heard the entire album in one sitting, "I loved it. It was a different sound. My background wasn't Hindi film music at all. It was much more Western. This was interesting because it was Hindi music but in tonality, arrangement, and form, it appealed to a Western ear as well. But most recording engineers thought he wouldn't make it, that his voice didn't work."

When Mathai asked what he could do for him, Ali told him that BMG, the recording company, agreed to print and distribute the album if he could get a music video done. Ali had told BMG he could get Mahesh Mathai, a known name in the ad-world, on board to direct the video and BMG agreed. Mathai acquiesced. "I agreed because he seemed like he was in trouble. He was also married and had a kid. Then he said, 'One more thing. I didn't tell you this, but you've got to pay for the video'."

Mathai, who was under the impression that BMG was paying for the video, was shocked. Ali explained that the deal actually was for BMG to only publish, print, and distribute the album, with a 50-50 profit sharing agreement between them and Ali. Mathai told Ali to renegotiate the contract; that he would shoot the film with his money, since Ali was broke, but that profits must be shared three-ways, between BMG (later Sony when they acquired BMG), Lucky Ali, and Mahesh Mathai. Mathai was dumbstruck when BMG agreed without pushback. "This has never happened before or since in recording album history. That [the director of a music video is] the owner of 1/3rd of the album's profits. Every December-January, even till last year, the accountants of Sony send a small cheque."

Mathai laughed when I asked if he storyboarded the music video. "It was all instinct". The circumstances were different because he wasn't answerable to anyone since it was his own money, "I was my own client." He was certain that he wanted to shoot it in the Arab world, but to also make it instantly recognizable he zeroed in on the Pyramids, a Wonder Of The World known to most Indians, even if they hadn't visited it. Mathai was clear that he wanted Ali to wear that headgear, and come on a bike, denim shirt, denim pants, "an Arabic look".

Ali's first wife Meaghan Jane McCleary, who then went by Maymunah, made an appearance in the video as the woman draped in blue. Mathai was shooting on the go — if we saw people smoking hookah and playing dominos, he shot it.

At that time Mathai spent 15 lakhs, a "shit-load of money" then, to get the crew to and from Egypt and to shoot the video on film. "It was a ridiculous budget, but I was doing well those years, so I took the chance." He recovered the entire budget from the profits of the album sales within two years.

There are two stories of how Sunoh's success played out. Mathai noted that the video and the album were an instant success. "The fact that BMG was giving us profits means they were making money. It was an instant hit, no question. Lucky Ali was unheard of before the album, and within less than a year he was being asked to sing Hindi movie songs. Lucky was getting mobbed straight away," he says.

A myth started being spun around Lucky Ali, aided by his own personality — working on oil rigs, breeding racehorses, selling carpets, marrying three times, divorcing once. He farms in Bangalore now.

However, music critic Narendra Kusnur, who was then writing for the tabloid Mid-Day noted that though people liked the video and there was notable word-of-mouth, the album slowly picked up over 4-5 months. It released in May, and it was only in November 1996 when the video and the album was awarded by Channel V that the buzz bubbled. Channel V pushed him and his video out, and soon this was picked up by local channels playing the video of 'O Sanam' alongside the best of bollywood music. Kusnur also observed how the other songs on the album — 'Milegi Milegi', 'Tum Hi Se', 'Pyaar Ka Musafir', and 'Yeh Mumbai Nagariya' — were gaining traction through album sales and the radio. Whatever the timeline, that it was a success is undisputed, having sold over 10 million copies.

Ali himself was not in India at that time. "I was so tired of running around trying to release it, that when the album was released, I said that I had done my work. I was in New Zealand. The song became what it became, but I never knew about it," he says.

Ali never set out to compose an album. His instinct was to travel, and within travel was embedded the instinct to make music. It was only later that he was told by close friends and family to compile his music and put it out as an album. When I spoke to him, his impression of his success was in that odd space between gratitude and indifference. "At that time, it was about doing something to show my parents that I was not bekaar. That I have thoughts. I have goals. Maybe I am not able to express it except through music."

Since the success of his first album he would puncture the music landscape of the time every few years before retreating. A myth started being spun around him, aided by his own personality — working on oil rigs, breeding racehorses, selling carpets, marrying three times, divorcing once. He farms in Bangalore now.

Tewari notes that the myth of Ali was so aligned with his truth, it was bound to make him a star in his own right. "He has an album called Rasta Man. The thing is he is a rasta man who lives his life on the road, traveling in his caravan. A few weeks ago when I spoke to him he was in Assam, and before that he was in Goa. So, it's not like you're making a brand out of nothing, it is who he is and it is reflected in his music. Because there is no lie."

By all measures Ali isn't a technically perfect singer. Kusnur has, in his reviews, written how he often is "be-sur". But his allure is not his talent, but his mood. When Kusnur first met him in 1996, reluctantly, during the PR push for Sunoh, they ended up speaking for an hour. "He had no airs about himself. When I asked if he would perform these songs live, he said, "Yahin kisi ke ghar mein bajaunga, chaar-paanch log ke saamne… utna confidence hai mere paas. But ask me to stand in an auditorium… that's not my cup of tea.""

25 years later, strumming the guitar among a newer crop of listeners, many of whom were too young or too unborn to have heard the song in 1996, he stops in his step again, "I'm nervous", he giggles as fumbles and moves on, singing the same song he sang for Kusnur at that rag-tag PR campaign, the same song that played on the radio without exhaustion, the same song that he has been singing since.