- Reviews

- Power List 2024

- Cannes 2024

- In-Depth Stories

- Web Stories

- News

- FC Lists

- Interviews

- Features

- FC SpecialsFC Specials

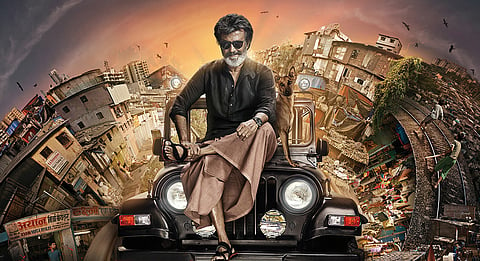

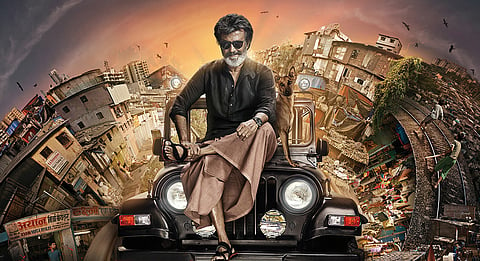

Director: Pa. Ranjith

Cast: Rajinikanth, Nana Patekar, Huma Qureshi, Aruldoss, Eswari Rao, Samuthirakani, Anjali Patil

Language: Tamil

Six years after Mullum Malarum (1978), director Mahendran and star Rajinikanth made Kai Kodukkum Kai, a sensitive drama now remembered mostly for the Ilayaraja beauty, Thazhampoove vaasam veesu. The film bombed. It's difficult to say why exactly a film fails — it could be a wrong release date, or maybe it wasn't publicised well, or maybe it just wasn't very good. With Kai Kodukkum Kai, however, there was another consideration, that the actor of Mullum Malarum had now become a huge action star, having made a series of hits (Murattu Kaalai, Thee, Moondru Mugam, Paayum Puli) in the intervening years. This resulted in Mahendran making some compromises, and Anandha Vikatan, in its review, complained that the film was stranded in between Mahendran-ism and Rajini-ism. I was reminded of this statement when I watched the first Pa Ranjith-Rajinikanth collaboration, Kabali. I remembered it again when I saw Kaala.

Tamil cinema has made villains of soft drinks manufacturing MNCs and organ-trafficking gangs

Can a filmmaker with a unique vision retain that uniqueness when the film stars a one-size-fits-all brand like Rajinikanth? This is not a new question. It came up when Mani Ratnam took the superstar on in Thalapathy. But because the story was a largely emotional one that spun variations on familiar beats — action, drama, relationships — the shoe fit. Ranjith, however, is a far more political filmmaker, and unlike Mani Ratnam, he isn't content to tell a story around his star. He wants his star to be the speaker through which he disburses his ideologies. In that respect, it must be said that Kaala is far more accomplished than Kabali — far more interesting as well. If Mani Ratnam looked at the Mahabharata, Ranjith takes his inspiration from the Ramayana — though not the traditional versions. His Ramayana is the one from rationalist readings by intellectuals like Periyar (whose name is found on a road sign in Kaala), which also cast the epic in an Aryan vs. Dravidian light. Not only did Rama become a bit of a bad guy (and a racist), the dark-skinned Ravana was reclaimed as something of a hero, whose kidnapping of Sita was simply an act of revenge for the cruelty Rama inflicted on his sister, Surpanakha. Hence the colour reversal in Kaala: the hero wears black, the villain floats in a sea of white (which includes his clothes, his walls and even the upholstery in his living room).

This is a story about land. Ranjith has always been invested in real estate and issues of ownership. In Madras, it was a wall fought over by political parties. In Kabali, the protagonist spoke of how Tamil labourers transformed a region of forests into present-day Malaysia, and were now being driven out of the country they helped build. Kaala begins with an animated prologue (oh, how Ranjith loves his scene-setting prologues!) about the urban poor in Indian cities, and zooms in on Mumbai, where slums spread out like the shadows of skyscrapers. This sounds like a ripe premise for a masala movie, with the land grabber as the villain. After all, Tamil cinema has made villains of soft drinks manufacturing MNCs and organ-trafficking gangs. A "social issue" is so often reduced to an easy target, so the hero can deliver clap-worthy punch dialogues about exploitation.

There's a terrific visual of Kaala striding grimly through a carpet of fire, but there's also a character named Shivaji Rao Gaekwad who gets killed

But the revised-Ramayana angle makes Kaala very different. (Ranjith revises it even further, by making his Ravana the father of four sons, one of whom undergoes a "vanavasam".) In a stretch towards the end (inexplicably staged in Hindi, with subtitles that are sure to be overlooked by many), we are told that each time a head of Ravana's fell, a new one would take its place. The subtext is absolutely revolutionary for a film with a megastar like Rajinikanth. It's not about a single hero. It's about a people's movement, where if the hero falls, someone else will rush to take his place and continue his work. The pre-interval scene emphasises this distance from routine heroism (though, like most other ideas in the film, it sounds better on paper than it plays on screen). The villain's car is blocked by angry masses. His associate asks if he should shoot them down. The sardonic reply: "How many bullets do you have?"

This stress on the collective results in the eradication (in a way) of the individual — never has Rajinikanth, who plays Kaala, been used this way, as practically a symbol. (Ranjith hasn't used Rajinikanth for what he brings to the table as an actor so much as what he stands for as a star.) There's a terrific visual of Kaala striding grimly through a carpet of fire, but there's also a character named Shivaji Rao Gaekwad who gets killed. There's a point you expect Kaala to cry, but the lamenting duties go to someone else. There's a point, after the smashing "Kya re? Setting aa?" line, where you expect Kaala to fight, but the action duties go to someone else. You expect the flashback to show a younger semblance of Rajinikanth (like we saw in Kabali), but the actor is replaced by an animated version. Rajinikanth, himself, is older. The Rajini-isms from his past (the Oho kick-u yerudhe song and dance from Padayappa, the two-heroine scenario from films like Veera) are refitted around a character with grandchildren, and even the fanfare behind the S-U-P-E-R S-T-A-R letter formation at the beginning is replaced with the siren we heard throughout Kabali, though in a much muted form.

This, I think, is the film Ranjith wanted to make, but because you cannot take Rajinikanth entirely out of a Rajinikanth movie, the superhero clichés crawl back in. Literally so — for the boy who goes to summon Kaala (this is the hero introduction shot) is seen in a Captain America T-shirt. And Kaala is left dangling between Ranjith-ism and Rajini-ism. Despite the empowerment of the masses, the story plays out for the longest time like a routine hero-versus-villain saga. The villain is a saffron-tinged politician, and Nana Patekar imbues him with his brand of subtle menace (and also gets to say magizhchi; in a further instance of subversion, the expression from Kabali is now uttered by the antagonist). But the character is severely undermined by having the actor dub his Tamil lines. He sounds like a tiger in Hindi and Marathi. He sounds like Kajal Agarwal in Tamil.

Adding to the narrative chaos, the ideator/ideologue in Ranjith seems to have taken over the writer/filmmaker in him. The ideas are great, and make you think: the death of a villain is usually intercut with the slaying of a demon, but here, we get shots of a god (Ganpati) being immersed. But what about execution? A pre-interval action sequence recalls the one from Madras, but without the bravura shot-taking. You could write a small thesis on the difference between the Ranjith of Attakathi/Madras and the Ranjith of Kabali/Kaala. Compare the fabulous way the breakdancers were incorporated into the choreography of Kaagidha kappal versus the suddenness with which Kaala's rappers invade the frames. Compare the electricity at the point where the protagonist of Madras threw paint on the wall to the gimmicky scene, here, of black powder being sprayed on the villain. We are a long way from the playfulness of the fractured tracking shots from Attakathi — the basic choreography of the scenes with Kaala's large family bring to mind the Fazil era, where the cast was lined up as though for a school assembly.

The most mystifying aspect of Kaala, in the context of a mainstream Tamil film, may be how ineffectual the deaths are

Even the writing feels different. There are some nice, wry bits like when a man from the slums realises what it's like to climb the many floors of a high rise in the absence of a functioning elevator. But the bigger scenes feel hollow. Remember how crushing Anbu's demise was in Madras? Ranjith fails to locate similar veins of sadness here. The return of a son into the family fold is glossed over, the reformation of a traitor to the cause is buried in a song — it's like Ranjith decided to do away with the usual emotions, but masala entertainers thrive on bursts of emotion, without which they wilt. The most mystifying aspect of Kaala, in the context of a mainstream Tamil film, may be how ineffectual the deaths are. A boy is found hanging, but we barely know him, so his mother's grief remains at a distance. Kaala's father is killed, but as this is depicted in animation, we are disconnected from Kaala's feelings — and even later, the death hardly seems to matter to Kaala. Now take the other Tamil drama based on the life of a Dharavi don, Nayakan — every time someone died, it felt like a hammer blow to the chest, and it changed the protagonist in some way. Here, Kaala is the same before and after a member of his family dies, so you wonder what narrative purpose the death served. Santhosh Narayanan works hard to elevate these scenes with his score, but his songs stand out more. A single line from Kannama (Aagayam saayamal thoovanamedhu) is more evocative than anything in the movie.

Maybe we are witnessing a new form of filmmaking, a breakaway: "agitprop masala." But I just saw a filmmaker who was so in love with what he wanted to say that he didn't care how he said it. How can you forgive the scene where the upper classes are reduced to caricatures, casually tossing off lines like, "60% of the people in Dharavi are criminals"? Where's the nuance? But you must give Ranjith this. His usual Easter eggs are everywhere — Ambedkar, Buddha (contrasted with a statue of Rama, in an upper-caste house), the colour blue running throughout (Kaala dresses only in black or blue) — but for the first time, he brings the Dalit undercurrent to the surface. It's explicit in the scene where the villain refuses to touch the water in Kaala's house.

Several characters are terribly underwritten. Huma Qureshi, who does a lot of mournful staring, plays Zareena, Kaala's former love. We also learn she is a single mother, a point dangled like it's going to go somewhere, until it doesn't. She's a world-renowned specialist in the rehabilitation of slums — "Namma Dharavi ya naama dhaan maathanum," she says (We should be the ones who change our Dharavi) — yet it doesn't seem to bother her that a developer proposes to waste 75 acres of Dharavi land on a golf course. (We know it's 75 acres because the characters have a way of passing on Ranjith's research as "dialogue." Elsewhere, we meet a girl whose name is the Greek word for "black." Fun facts, for the price of a ticket and popcorn!) Anjali Patil shows up as an activist. By the end of the film, I was still waiting to know what happens to her. And the mongrel that featured so prominently on posters wanders about with a lost look, as though someone forgot to feed it its lines.

This is nothing Rajinikanth hasn't done before, but it's still fun to be reminded of his instincts for comedy

But Eswari Rao, as Kaala's wife, transforms a one-note character into something very special. She has a smile that lights up the skies and the film's energy levels shoot up whenever she's around. (Ranjith writes older women really well: the shrill mother in Attakathi, the mother prone to emotional blackmail in Madras, and even Kumdhavalli from Kabali, who was easily the film's most interesting character.) Samuthirakani is characteristically terrific. I wish he made fewer films and acted more — he nails a drunk's exaggerated efforts at appearing sober. Manikandan, as Kaala's son, brings a very palpable anger and sadness — the character is one of the more interesting ones, an anti-rowdy, in contrast to his father. (He believes in peaceful protests like the one in Thoothukudi.)

And Rajinikanth? What do you say? It's nothing he hasn't done before, but it's still fun to be reminded of his instincts for comedy. His eye-roll when his wife speaks in English is spectacularly funny. His punchline delivery is sharp as ever, but the role assumes another dimension due to the actor's politics. Of course, here he is an actor mouthing someone else's lines, but the effect of his recent public statements hangs like a shadow. An early line goes, "Kodi pazhasaana erakki thaaane aaganum! (You have to lower a flag when it gets old.) A statement? I don't care, frankly. I'm just glad the two-film deal is over. Now, Ranjith can go back to being Ranjith, and Rajinikanth (on the evidence of Karthik Subbaraj's statement that his film with the superstar is an apolitical entertainer) can go back to being Rajinikanth.