- Reviews

- Power List 2024

- Cannes 2024

- In-Depth Stories

- Web Stories

- News

- FC Lists

- Interviews

- Features

- FC SpecialsFC Specials

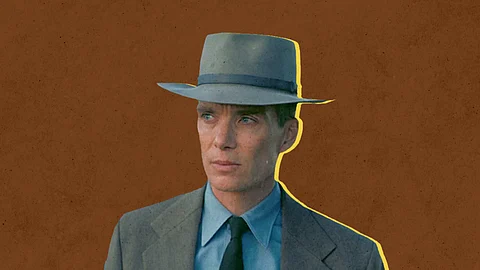

From the blaring brass in Inception to the soft piano and strings in Interstellar, sound has played a key role in every Christopher Nolan movie ever. In the case of Oppenheimer, however, the sound is the skeleton of the film. Without it, even Cillian Murphy's piercing gaze wouldn't have its profound effect on viewers. It not only builds the anxiety of what is to come in everyone's heart but also gives the audience a snapshot of what is happening in our flawed protagonist's mind. The combination of a brilliant musician like Ludwig Goransson, strings, some mild bass, and of course, the blaring horns and explosions, Oppenheimer perfectly builds a marvellous, yet haunting cinematic experience for audiences to witness.

When we first meet Oppenheimer, he is somewhat of an outcast. Emotionally challenged and homesick, he knew that his heart lay somewhere else, so much so that he is distracted in the Chemistry laboratory. However, the moment he encounters renowned physicist Niels Bohr, his interest spikes. As much as he wants to know more about quantum physics with him, he admits that he is not fond of math, to which Bohr replies, "It is not whether you can read sheet music or not. What matters is whether can you hear the music." Immediately Goransson's soundtrack kicks in with violins going in a fugue-styled tune, increasing in tempo as his interest in quantum physics rises. It was as if the subject was music to his ears. Even when he is teaching it at Berkley, the same tune plays, albeit slowly. It is as if the score is implying that he was the happiest when he was one with the subject and imparting his knowledge to other students. However, as the tune progresses, the horns come blaring in, as a warning of the destructiveness it possesses. We see Oppenheimer get consumed by his passion oblivious to the destruction that is to come.

As the film progresses, we see Oppenheimer encounter physicists and politicians who have a stake in the matter and we see that the once gentle, yet glorious score starts to become more and more discordant, especially when it approaches the Trinity Test. The iterations of what can be termed as the love theme of Oppenheimer and quantum physics are irregularly interrupted by his visions of an atom splitting and the massive consequences it can bring, or even something as "harmless" as a ripple effect caused by a raindrop. At times, the score poses as a facade, pushing forth Oppenheimer's prowess while hiding his apprehensions and fears.

Even when the preparations start for the Manhattan Project, the glorious strings are met with discordant notes and blaring horns, literally implying that they were playing with fire. It also highlights the urgency his team is met with as they race against the Nazis to first create the bomb. Here is also where we get a glimpse of the small explosions being tested before the atomic bomb is tested. If one notices carefully, first the explosion happens, then the sound comes. This plays a key role in the final atomic bomb explosion we see in the test. As per the laws of physics, light travels faster than sound, which is why there is a slight delay in the sound of the explosion reaching the spectators. So when the final test happens, audiences cannot help but look in awe at the flames shining bright, only to be rocked by a deafening explosion.

Probably one of the best uses of sound in the movie is during the scene when Oppenheimer addresses the crowd after the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings. As much as he wants to mean every word he says, his conscience is rattled. So much so, that he cannot distinguish between the audience's cheers and the horrifying cries of anguish of the victims. At some moments, he cannot even hear those cheers as what he can only feel in his mind and his heart is a profound emptiness and pain. This one scene alone not only haunts Oppenheimer but us audiences too, especially since we are aware of the irrevocable damage the bombings caused to Japan.

In many ways, the score and the sound design compare Oppenheimer's journey to that of an atom splitting, fascinating to ponder on but highly destructive. As he comes to the grim conclusion that his efforts may have resulted in not a chemical, but rather a political chain reaction which can destroy the world, we hear his once glorious love theme, but now it is marred with an imperfect cadence, mirroring the guilt and regrets that always lived with him and leaving us wondering that in our relentless pursuit of power and technology, have we already crossed the point of no return.