- Reviews

- Power List 2024

- Cannes 2024

- In-Depth Stories

- Web Stories

- News

- FC Lists

- Interviews

- Features

- FC SpecialsFC Specials

Director: Kabir Khan

Writers: Kabir Khan, Sumit Arora, Sudipto Sarkar

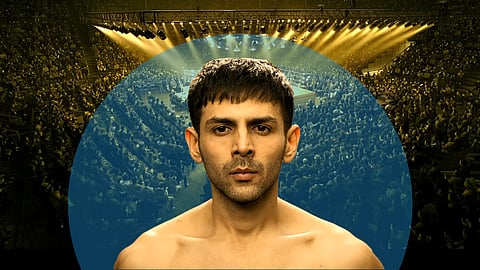

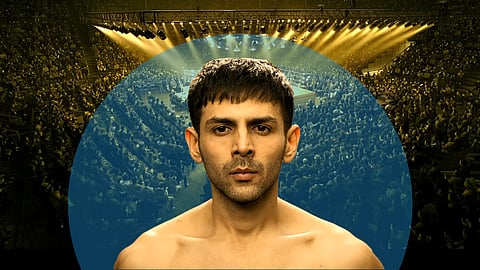

Cast: Kartik Aaryan, Vijay Raaz, Bhuvan Arora, Yashpal Sharma, Palak Lalwani

Runtime: 143 minutes

If you review Hindi films every week, chances are that the “biographical drama” strikes fear in your heart. There is no escape (or escapism). Most biopics are great stories looking for an excuse – rather than a medium – to be told. All that matters is the significance of the life in question. The cinema of it all is incidental. But Kabir Khan’s Chandu Champion is a great story that reclaims the medium of film-making. Unlike his previous film, 83 (2021), at no point does Chandu Champion rest on the acclaim of its subject alone. Every scene is a little better because it’s shot; every moment is an adaptation of the truth. The craft doesn’t impress, it expresses. The camera doesn’t just show, it reveals.

This tale of India’s first Paralympics gold medallist, Murlikant Petkar, follows the conventional sports biopic template. But I didn’t think a film so familiar could be so effective. The dismantling of my skepticism brought back memories of watching Ek Tha Tiger (2012) and Bajrangi Bhaijaan (2015), two Kabir Khan hits that enhanced the basics of their genre. Solid action choreography. Catchy soundtrack. Ambitious cinematography (including a one-take war sequence in Kashmir). Well-timed and poignant background score. Skillful staging. Smart training montages. Easy rhythm. Creative transitions. None of this is extraordinary; it’s just an extra layer of spirit coating the ordinary.

For starters, Chandu Champion is surprisingly lean in terms of narrative scale. This is the expansive story of a small-town man who joins the army to sustain his dream of winning an Olympic gold medal, suffers crippling bullet wounds in the 1965 war against Pakistan, and claws his way back as a champion para athlete in an ableist system. But the film is defined by what it subtracts – and by extension, what it chooses not to be. It resists the temptation of bullet-point excesses. You see Murli’s childhood, his passion for wrestling, his army days, his switch to boxing, his injury, and his record-breaking feats as a disabled swimmer in the 1972 Munich Games.

But there’s nothing about his success in other events like javelin throw and slalom. There’s nothing about his table-tennis exploits in the 1968 Games. There’s no romantic track. There are no signs of his future wife. There’s no prolonged struggle for recognition (the primary timeline is that of a 73-year-old Murli making a case for an Arjuna award so that his underdeveloped village inherits his spotlight). There is no performative patriotism: The national anthem is not heard but ‘seen,’ through the image of a stadium rising in honour of an Indian seated in a wheelchair. The first appearance of the tri-colour: Murli wakes up from a two-year coma and mistakes a senior officer for an enemy soldier, only for a glimpse of the flag to serve as his proof of location. One might argue that the narrative is selective, or that it amounts to erasure. But it’s very much the opposite of that. By picking a lane, the film commits to the identity of a person, not the landmarks of a personality. It commits to the soul, not the body.

Even the tired tropes find meaning here. For instance, the default setting – of an old Murlikant narrating his story at a police station – is hardly new. But the slew of fine supporting actors (Shreyas Talpade as the inspector; Brijendra Kala as a nosy prisoner; Pushkaraj Chirputkar as an anxious constable) raises the bar a bit. The childhood portions of a 9-year-old Murli getting mocked (‘Chandu’ means loser) and triggered by people laughing at him earns a nice callback in a future newspaper article (“Why are you laughing?” captures the essence of self-belief). When Murali travels abroad for the first time, there’s inevitable culture-barrier humour: His lack of education and English-speaking gaffes make for an extended gag. But the impeccable comic timing of Bhuvan Arora as Murli’s best friend makes the difference. A pre-interval tragedy is amplified by the high-stakes design of a long unbroken shot connecting peace and war; the death of a character lands a little harder because of the film’s technical urgency. A hospital portion full of Munna Bhai-style nurses, clerks and patients is so sappy that it works. A journalist does an article on Murli so that we understand the film’s central metaphor – Murlikant’s journey is actually his young and bruised country’s journey into independence. When she spells it out, it feels like a revelation, not something that was obvious all along.

Most of the formulas work because of the way Chandu Champion is written. It’s a real-life story, but it embraces the fact-is-stranger-than-fiction aesthetic. It unfolds with the fantasy and fluidity of a Forrest Gump-like film. Take, for example, the cameos of history in his story. In his first scene, little Murli is seen cheering at a packed railway station for Khashaba Jadhav, independent India’s first individual medal winner at the 1952 Helsinki Olympics. Murli idolizes Dara Singh, the near-mythical wrestler whose longevity becomes the catalyst of his paralympic ambitions – Murli’s mentor Tiger Ali (Vijay Raaz) takes a paralyzed Murli to watch a 40-year-old Dara still fighting, still battling, to chase an incomplete dream. A hospital clerk’s gambling habit brings Murli in contact with ‘Matka King’ Ratan Khatri, whose prophecy (“everything you touch turns to gold”) fuels his second shot at a gold medal. His journey even collides with the 1972 Munich massacre, a clumsy but emphatic way to suggest that Murlikant Petkar’s life is inextricably linked to the legacy of sport. For a film that revolves around someone whose credentials are lost in the folds of the past, these little historical intersections become an indentation – a live-action résumé – of his footprints. There’s evidence of Gump in a few other motifs as well: The narration to strangers, an era-starting sprint away from bullies, a dysfunctional family, an army stint, his attachment to his boss, the media coverage, a nation that becomes synonymous with him. Perhaps that’s why his table-tennis gig and love story find no mention; the similarities might have been too blatant.

What this tone also does is set the stage for a remarkably potent climax. Again, it’s a case of minor calibrations to a familiar template. On paper, it’s the same: A race, the suspense, a slow-motion finish, a life-flashing-before-eyes montage. But the way it’s done perfectly feeds the sport of swimming – every time Murli’s face surfaces to breathe, he sees a different chapter, a bygone memory, outside the pool. Every gasp for air feels like an admission of oxygen. Every stroke feels like a stroke past his struggles, not away from them. The sport itself feels like an extension of his underwater-to-breathing ratios of life. It’s far more seamless than a regular flashback because it merges plain sight and hindsight, his story and history, without any visual jerk.

Kartik Aaryan’s physicality plays a key role in these moments. Despite his conscious movie-star smile, this is a performance nearly bereft of vanity. Maybe the synchronization of desire has something to do with the actor trying as hard as his character. It’s his desperate body language that tides over the cracks of his language. At some point, you almost forget Aaryan’s jarring take on Maharashtrian Hindi: Murli’s “main jeetega” is an awkward ode to a 16-year-old Sachin Tendulkar’s “main khelega” after being hit by a Pakistan bowler’s bouncer. His pronunciation of “Champion” sounds more like a riff on West Indian cricketer Dwayne Bravo’s 2016 anthem than a modest Sangli man’s tryst with a non-Marathi word. But his slips stop mattering because, for once, Aaryan transcends his derivative style. There are always shades of other actors – Akshay Kumar for comedy, Ranbir Kapoor or Shah Rukh Khan for drama – in his performances. At times, he plays innocence as a medical condition or passion as a literal version of madness. But the role of Murli forces him to shed the Bollywood hangover and look towards life itself. The result is far from perfect, but it’s a big leap in the context of a commercial biopic.

It’s tempting to say that Aaryan is ‘shielded’ by the supporting cast. Yashpal Sharma is hilarious as tough-love-dispensing army boss; Vijay Raaz’s reaction shots continue to be terrific payoffs; Rajpal Yadav is entertaining; Aniruddh Dave excels in one of the film’s best scenes as Murli’s heartbreaking older brother. But Aaryan holds his own with and without them. The film knows how to use him. If anything, the directness of his emotions informs Murli’s shapeless thirst for greatness. It leaves plenty of room for interpretation. Is his quest selfish? Perhaps. Selfless? That too. Crazy? Of course. Patriotic? Naturally. None of the above? Maybe. You just go with the flow because Chandu Champion strips a story down to bouts of feeling. Every time he gets knocked down, the anticipation of a comeback keeps you going. You know exactly how that comeback will look, but that’s not the point. You expect to be manipulated and moved, but it’s still comforting. Because good mainstream movies don’t swim against the tide, they surf on it. They don’t chase originality; they refine the art of predictability.