- Reviews

- Power List 2024

- Cannes 2024

- In-Depth Stories

- Web Stories

- News

- FC Lists

- Interviews

- Features

- FC SpecialsFC Specials

Directors: Coodie Simmons and Chike Ozah

Cinematographers: Coodie Simmons and Danny Sorge

Editors: Max Allman and JM Harper

Streaming on: Netflix

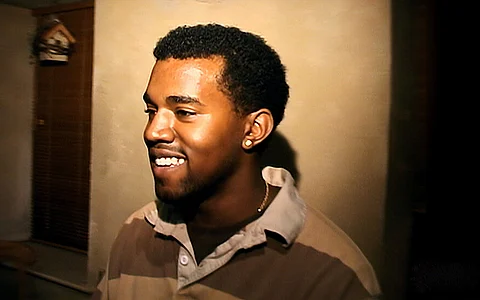

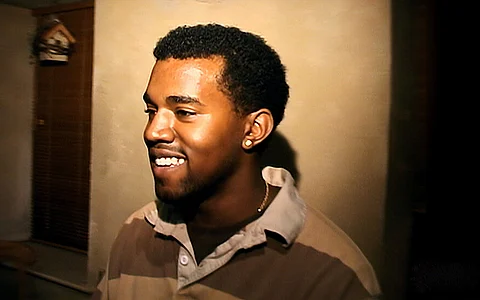

Jeen-Yuhs, the title of Kanye West's three-part documentary, feels like a cheeky in-joke, given how it functions as a descriptor for a man who once called himself "Shakespeare in the flesh", compared himself to God and launched a bid for the US presidency two years ago. What? it seems to retort. As if this documentary could ever be called anything else. But filmed with an affection that borders on a single-minded devotion, Clarence "Coodie" Simmons' four-and-a-half-hour-long film is less about navigating the rapper's planet-sized ego and more about reminiscing how he got pulled into its orbit. What emerges at the end is not only a compelling visual map of an artist's stratospheric trajectory, but also a tragic portrait of a director as enamoured by his subject as his subject is by himself.

It's love at first sound bite. Coodie, a standup comic and host of public access show Channel Zero meets Kanye, then a music producer, at Jermaine Dupri's birthday party in 1998. Gripped by this emerging talent, he quits his job and begins trailing him around with a camera. The initial portions of the documentary bear this freewheeling energy of a director who, in working with an artist yet to become a mainstream success, doesn't have a pre-made narrative template to adhere to. He's just along for the ride. But by the end, it's to both, the benefit and detriment of Jeen Yuhs that it's as unvarnished as it is. Less of a polished documentary and more of an intimate home video, it's a sharp contrast to the filtered, curated images of most modern artists. Even if the end result is as outsized and unwieldy as its subject, it's still just as compulsively watchable.

Coodie's voiceover becomes the connective tissue of this film, which spans two decades and is split into three parts. The first two of these chronicle Kanye's ascent, and the third, his downfall. "I be needing a translator real bad sometimes," says Kanye early on in Jeen Yuhs, a self-aware request the director takes seriously, providing context to most scenes and only occasionally framing his thoughts in overly ponderous terms. Example: "The more time I spent with Kanye, the more I wanted him to win. But I also saw how everyone played him." Visuals of a revolving door of rappers asking Kanye to produce their tracks, and in one case even declining to pay for his work, cement the idea enough that the voiceover didn't need to reiterate it. Coodie faithfully documents Kanye's struggle to cross over as a rapper as it unfolds, but can't resist the occasional dramatic flair. He's fond of ending scenes in the first installment by gradually lowering the volume of Kanye's voice mid-speech and layering it over swelling music, as to reinforce the idea of an artist just on the cusp of greatness.

Kanye's hunger for recognition is matched by a limitless bravado, which the all-access documentary is around to capture in minute, fascinating details. In one scene, he shows up at Jay-Z's Roc-A-Fella Records, takes off his retainer and starts rapping along to a track on a demo CD that ends with a roar of applause. In another, he talks about how, unable to afford a cab, he once ran 20 blocks to a studio because he wanted executives to hear his beats before they left. From this younger, humbler version of Kanye, it sounds believable.

The film is its most invigorating in its early stretches when it simply zooms in on Kanye and lets him freestyle endlessly, though the rapper's musical expertise is an area in which he still comes off as inscrutable. For all the talk of Kanye's genius, it remains a descriptor applied to the end result, rather than the process. Scenes feature him playing finished or near-finished versions of his songs with little insight into how they were created. Verses spring from Kanye's brain almost fully formed, and as impressive as they are, they offer no clue as to how he refines his writing. Raw audio of a choir singing 'We Don't Care' is eventually polished, without the viewer ever seeing how it's done. Still, it's hard to fault the lack of technical detail in a documentary in which the level of personal access makes the viewer feel like part of Kanye's crew, hanging out with him, driving around with him, even peering into his fridge to discover a bag of peas and a half-empty sauce bottle, a shot that carries a startling intimacy.

Jeen Yuhs juxtaposes a rapper and his director who gradually come to realise that they're creating history, with record labels that seem reluctant to commit to a future. This version of Kanye has accrued enough goodwill to be able to get other artists to lend him some of their studio time when his label doesn't have the budget to get him a slot of his own. He has friends, and fans, in Jay Z and Pharrell Williams. "Closed mouth don't get fed," Jay Z tells him, referring to how if Kanye hadn't been brave enough to ask, he wouldn't have scored a verse on Jay's new album. It's a line that reverberates with chilling prophetic power when Kanye gets into a car accident, shattering his jaw in three places soon after. Undaunted, he draws rhymes from the wreckage, writing and recording his debut single 'Through The Wire' with his mouth wired shut.

This stretch is when it becomes evident just how much the documentary's fly-on-the-wall approach contributes to its allure. Kanye's dentist explains the extent of the damage and the intricacies of rebuilding a shattered jaw, a process that includes physical therapy and eventually, rebreaking the bones to set the teeth. None of this is said to camera — the dentist visibly bristles at the intrusive presence — or in service of the documentary. The dentist is simply a man doing his job, and Jeen Yuhs is all the richer for it.

In the third episode, however, Kanye's fame and the home-video intimacy gives way to stock footage of the rapper on talk shows and at concerts stitched together to convey the impression of a man so consumed by playing a part, he forgets which of his personas is the act. Coodie's voiceovers grow less insightful, lapsing into stock platitudes. The director, who adopted the professional role of a spectator, is hurt to discover he's on the sidelines of Kanye's personal life too. His filming of Kanye's journey never appeared to be motivated by an opportunistic business sense, but through the rapper's brusque dismissals of him, you begin to wonder if Kayne sees it that way. As the distance between them grows — at one point, they don't speak to each other for six years — he charts Kanye's fall from grace through archival footage, including that of President Obama calling him a jackass, interspersing it with charming home-video clips of his daughter growing up. If the intent is to depict that his sights are set elsewhere, that he's far removed from the musician's world, the effect is the opposite. The unkind contrast between Kanye's spiral into darkness and the inherent lightness of a playful child feels like an overcompensation, highlighting how Coodie misses his old friend more than ever.

The major flaw of Jeen Yuhs becomes apparent here. It chronicles, but never questions. It captures, but never criticises. The documentary depicts Kayne's boundless affection for his mother, but never probes his misogynistic attitudes towards other women, from his statement about having to take "30 showers" after dating model Amber Rose to the exploitative nude waxwork figure of Taylor Swift he used in his 'Famous' video. It devotes cinematic space to Kanye talking about his spiritual beliefs, but doesn't reconcile that with his decision to support President Donald Trump, a man associated with the distinctly un-Christian acts of racism, fraud and sexual assault. Jeen Yuhs gives Kanye the platform to explain himself, which he does by defending his freedom of speech and framing it as part of a divine plan, but without Coodie to act as a translator, he might as well be speaking a different language. That the rapper's affinity for looking sharp translates into a fashion line feels like a natural progression over three episodes, that his natural talent for showmanship morphs into the aggressive, headline-grabbing Kanye of today, less so.

Coodie constructs two contrasting images of a man, getting audiences to question what changed in between, but his lack of perspective regarding this change makes Jeen Yuhs ring hollow. In its most touching moments, the documentary cuts away from a Kanye rant, affording him a measure of privacy as his mental health deteriorates. At its most simplistic, it makes excuses for his behaviour. Early on, Kanye says his dog was named Genius because he could get out of any cage they put it in. The documentary seems to be Coodie's way of affirming that he has the same confidence in his subject. Four-and-a-half hours later, however, more critical viewers will sympathise with the feeling of being caged in, yet still find Coodie's confidence misplaced.